October 19, 2016

As a dentist, Thomas Nabors was attentive to his own mouth and he took good care of his teeth. But he was also acutely aware of the role that bacteria plays in oral health, and he had seen numerous studies linking gum disease to heart problems. So even though he didn’t have other cardiovascular risk factors—he wasn’t overweight and never smoked—he decided to undergo testing. It may have saved his life: he discovered that his carotid arteries were clogged, restricting blood flow, and the vessel walls were inflamed. It meant that he had a 50-50 chance of having a heart attack or stroke.

Oral bacteria were found amidst the plaque inside Nabors’ heart vessels, making it a likely source of the inflammation. So Nabors investigated further, checking for an imbalance of bacteria in his mouth, using a saliva test he’d developed. He then asked his son, Thomas Nabors III (who is also a dentist), to give him a thorough exam, adding the extra step of getting a CT scan. Sure enough, those tests revealed extremely mild gum disease that had not yet produced symptoms, but even these “subclinical” infections can deliver bacteria into the bloodstream.

His son treated the periodontitis with a personalized antimicrobial therapy developed for cases like his. Within two months, follow-up tests showed the arterial inflammation had subsided and the plaque had stabilized, sending his risk plummeting. “Today my risk is very close to zero,” says Nabors, 73, who has retired from dental practice but still teaches at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Nashville. Because he was proactive, Nabors was more fortunate than many.

In 2000, in his Oral Health in America report, then-U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher declared that poor dental health was “a silent epidemic promoting the onset of life-threatening diseases, which are responsible for the deaths of millions of Americans each year.”

The report sparked awareness that the mouth is not separate from the rest of the body and oral health is vital to general health and welfare—and must be integrated within an overall healthcare plan. Towards that end, in 2005, New York University announced a radical plan to combine its dental and nursing schools.

The change was not readily embraced by all, with much of the pushback coming from the dental profession, says Michael Alfano, who was then dean of the College of Dentistry. “There was a perception that it was upsetting the paradigm…but the paradigm needed to change.”

A decade later, the fields of dentistry and medicine are slowly merging, both in the U.S. and across the globe. A mounting body of evidence is connecting the inflammatory processes that cause gum disease with other medical conditions. Research is revealing how the health of teeth and gums, along with certain microbes commonly found in the mouth, impact overall, whole-body health. “Now you’re seeing quite a bit of emerging evidence that a healthier mouth has beneficial effects on the body,” says Marko Vujicic, chief economist at the American Dental Association’s (ADA) Health Policy Institute.

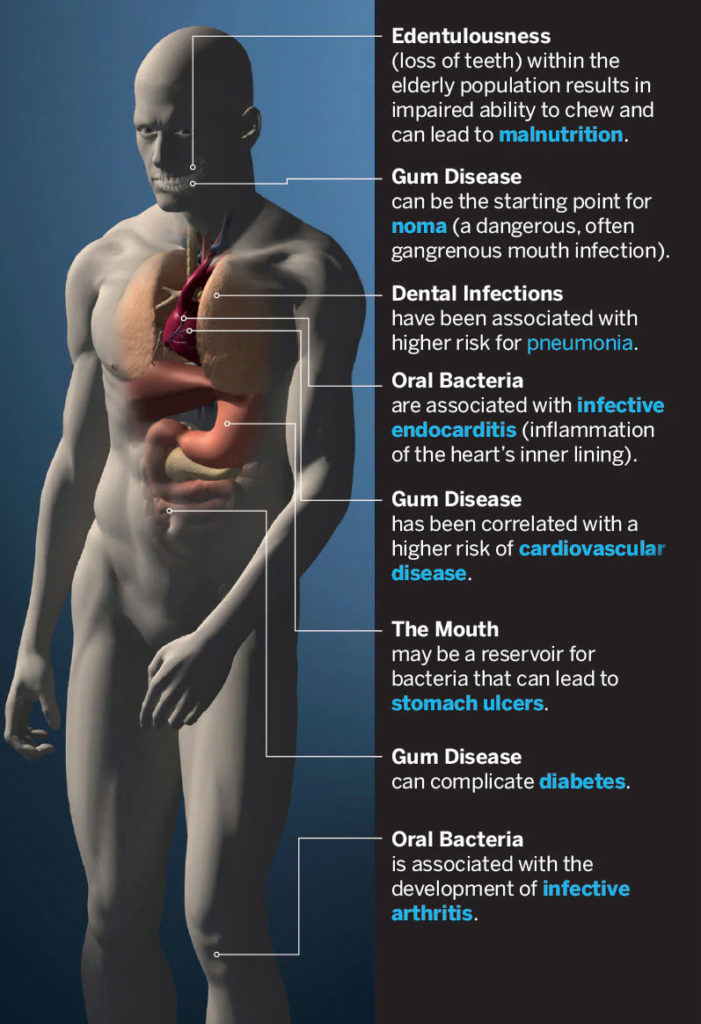

Researchers have known for about half a century that periodontitis—swelling, bleeding and receding gums—is caused by an imbalance of oral bacteria. The condition destroys gum tissue as well as the ligaments and bone that anchor teeth within the mouth. But ongoing studies are revealing more serious implications: gum disease may also raise the risk of serious or life-threatening health conditions, from stroke and pneumonia to heart disease. It may worsen diabetes (which, in turn, exacerbates gum disease) or may bring on early labor, giving premature babies a tough start in life. The enzymes, chemicals and bacterial toxins that are part of the inflammatory process in the mouth may also cause cell mutations, changes that could eventually progress to oral cancers.

Poor oral health and recent dental procedures have also been targeted as one cause of endocarditis, a potentially fatal heart valve infection that was first described in 1885—which highlights one of many reasons that preventative care is imperative.

Oral Report

The prevalence of caries, or cavities, in adult permanent teeth makes tooth decay the most widespread health condition across the planet, according to a 2013 study led by researchers at Queen Mary University of London. Untreated tooth decay affects one-third of the world’s adult population, more than 2.4 billion people. An additional 11 percent—743 million people—suffer from severe periodontal disease. At least 158 million individuals have lost all of their teeth.

But dental disease is not limited to adults. Worldwide, untreated cavities in baby teeth is the most prevalent chronic health condition in children. For example, at least 70 percent of Indian children suffer from decaying teeth, according to the World Dental Federation’s Oral Health Atlas.

Svante Twetman, a professor who studies tooth decay at the University of Copenhagen, finds these numbers embarrassing. The cause, he says, is “too much sugar, too little fluoride, and too little cleaning.”

Lifestyle factors such as diet and hygiene are sometimes worsened by the inability to get care, either because of availability or cost. Those who live in areas where there is little or no access to dental care—or sometimes even to toothbrushes and toothpaste—fare the worst, and these are often the people who are most uninformed about oral hygiene. This seems to be true across the world, from developing countries in Africa, Asia, or Latin America to impoverished regions of wealthier countries.

In Spain, a nationwide dental study found that young adults from lower socioeconomic groups had twice as much untreated tooth decay as their wealthier compatriots. This also holds true in the United States, for example in Appalachia and parts of the South. A recent report by the Pew Charitable Trusts found substantial, economically driven racial disparities in dental health among U.S. children. National Health Statistics data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that untreated dental decay among 2- to 8-year-olds was 10 percent among white kids, 19 percent among Hispanic children and 21 percent among African American children; overall, 43 percent of preschool children had untreated decay.

Sugar is a huge factor. While eating some sugar won’t necessarily rot teeth, sipping soda, juice, or sports drinks or sucking on sugar-sweetened mints frequently during the day can damage teeth. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that no more than 10 percent of a day’s calories come from added sugar. Surprisingly, residents of some of the poorest African and Asian countries have less tooth decay than those living in Europe and North America simply because they eat less sugar, according to WHO. That’s changing, however, as people in even the most remote corners of the globe gain ever-greater access to processed and sweetened foods. “If we could just get people to change their behavior in terms of nutrition, it would be huge,” says Carol Summerhays, president of the ADA. She notes that limiting sugar intake not only preserves teeth, but also helps in the fight against type 2 diabetes.

This oral health crisis has sparked a global push to integrate dental care and medical care, and to improve access to dentistry. It’s pressuring governments to provide better dental care for children and the elderly and to expand education on proper oral hygiene, particularly among the poor. WHO is now encouraging school curriculums to include oral hygiene in school health programs.

Head Start, a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services program that helps low-income Pre-K children prepare for school, includes an oral health component. The program ensures that infants and young children have access to dental care, fluoride treatments, and any necessary medications. It also educates kids and their caregivers about the importance of oral hygiene and visiting the dentist, using a guide developed by Colgate that includes information on brushing, flossing, nutrition—and limiting sugary foods. This guide is part of the company’s “Bright Smiles, Bright Futures” program that sends a fleet of mobile dental vans to about 1,000 communities each year, offering free dental screenings to some 10 million children.

Another US campaign, the 2MIN2X initiative, encourages parents to teach their kids to brush for two minutes, twice a day, to fight cavities. A dedicated website offers two-minute videos for children to watch while they brush, and a “Toothsavers” phone app challenges them to save the residents of a fairytale kingdom from a tooth-rotting spell cast by an evil sorceress—by brushing their teeth.

The World Health Organization promotes water fluoridation as a broader public health solution, which Summerhays says is extremely helpful in fighting tooth decay. Community water fluoridation launched in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 1945; within 50 years, tooth decay had dropped by 25 percent and the CDC listed fluoridation as one of the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century. By 2012, the initiative had reached three-quarters of U.S. citizens. Although some 25 countries have established similar community programs, in 11 of these, fewer than one-fifth of the population drinks fluoridated water.

Longer in the Tooth

One of the most pressing global challenges to dental health is an aging world population. While the good news is that we’re living longer and tooth loss no longer has to be a natural part of growing older, “we [are seeing] a dramatic increase in root caries,” says Twetman.

With age, people grow “long in the tooth.” Gums recede, exposing roots that had been protected from decay. The process may be exacerbated by certain medications that are commonly prescribed to the elderly, drugs with side effects such as dry mouth. A lack of saliva not only promotes cavities, but along with swallowing difficulties, it increases bacteria in the mouth, which can cause gum disease or even pneumonia if it’s inhaled into the lungs. Across the globe, pneumonia remains the deadliest infectious disease.

But many senior citizens never see a dentist. Despite the complex needs of the elderly, oral health care for older, infirm people who are homebound or confined to nursing homes is sometimes overlooked altogether.

Treating the Whole Body

Meanwhile, the logistics of dental care are changing. Many dental schools are now training their students to practice in a collaborative, team-based manner, says Richard Valachovic, president of the American Dental Education Association. It’s part of a larger trend to integrate the healthcare landscape and make care more accessible. He uses the local drug store as an example. “Pharmacists didn’t think of themselves as healthcare providers 10 years ago,” he says, adding that today, they administer vaccines that once required a visit to the doctor’s office.

Dental offices can provide patients with an entrée into the healthcare system by screening for common health problems: at least 20 million Americans who go to the dentist each year do not see a doctor. Among them, “there are millions of hypertensives; there are a couple of million undiagnosed diabetics,” says NYU’s Alfano.

According to the New York State Health Foundation, about a quarter of people with diabetes and up to 90 percent of pre-diabetics don’t know they have high blood sugar—while roughly 13 million U.S. adults don’t realize they have high blood pressure, according to the CDC. Major health problems could be avoided by many if a standard dental exam added a blood pressure cuff and a finger-prick blood test to monitor for hypertension, high cholesterol and elevated blood sugar.

“This is really an unrealized healthcare opportunity,” says Ira Lamster, a professor of health policy and management at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “You don’t have to send the patient to a lab or send them back to a physician [for tests] because they’re already in the office,” he says. Some practices, like Delta Dental of New Jersey, are beginning to incorporate screenings for hypertension, diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea as part of standard care.

Some health centers in the U.S. have begun integrating dentistry into their practices, with dentists seeing patients in the same clinics as general practitioners, gynecologists, pediatricians and others. The Erie Family Health Centers in Chicago, for instance, have added full dental services to four of their 13 locations.

Because of his close shave with heart disease, Nabors urges his students to always get complete medical histories from their patients. His son, Thomas, has seen the value of this first-hand in his own practice. One of the most dramatic examples came during a routine screening when a middle-aged woman told him she had shortness of breath and pain in her arm. Her primary care physician had attributed the symptoms to asthma, but Thomas was concerned. He referred her to a cardiologist—who discovered that four of her coronary arteries were severely blocked, requiring immediate, life-saving bypass surgery.

A study published in 2014 by researchers from the State University of New York at Buffalo quantified the benefits of a more integrated dental-medical model. As part of patients’ regular dental appointments, they tested the blood sugar levels of 1,022 people age 45 and older. About 41 percent had elevated numbers and were referred to doctors. Almost a quarter of those proved to be pre-diabetic, while another 12.3 percent were diagnosed with full-blown type 2, or adult-onset, diabetes.

Since diabetes also impacts the mouth, screening during a dental exam has clear benefits. People with diabetes develop gum disease at about three times the rate as those with normal blood sugar levels, and as their gums recede, they often develop cavities in the exposed roots of their teeth. They are more vulnerable to Candida, a type of yeast that can infect the mouth, and may suffer from burning sensations in their mouths or painful, swollen salivary glands. Other evidence shows that people with diabetes and moderate to severe periodontal disease are twice as likely to have kidney problems. There are feedback loops in the other direction, too: tooth loss from severe periodontal disease makes it harder to eat well, making it more difficult for those with diabetes to manage blood sugar.

Regular dental care that addresses broader issues not only makes us healthier, but it saves money, too. A 2016 study published in the journal Health Economics examined insurance claims from 2006 to 2011. Researchers found that when newly-diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients were treated for gum disease, within three to four years their healthcare costs were about $2,000 less than those who were untreated. Even though medical and dental insurance in the U.S. are separate entities, some health insurance companies are now realizing that it’s better for their bottom line to offer dental coverage to diabetic patients.

‘Part and Parcel’

Despite the potential for improved wellbeing and lower costs, much of the world has not yet integrated dental and medical care. One exception is Malaysia, where the Ministry of Health has made dentistry part of its overall health system. The government provides dental care for some 80 percent of the country’s population, says Rahimah Abdul Kadir, pro-chancellor of Lincoln University College in Petaling Jaya and former dean of the college’s dental school. In Malaysia, dentists make annual visits to schools and children’s oral care is fully covered until they turn 18. Because pregnancy often causes inflammation and bleeding of the gums, prenatal clinics offer free dental checkups. Basic services such as fillings, extractions, and dentures are available for adults at low cost.

Outreach teams travel into the countryside to provide services to those who don’t live near clinics. Kadir notes that as part of a commitment to meld oral and medical care, “we’ve developed health centers where dental care is part and parcel of the whole clinic. We don’t actually have special dental clinics standing all by themselves. That was the old days.”

As former president of both the Asian Academy of Preventive Dentistry and the South East Asia Association for Dental Education, Kadir has a broad perspective on the general state of oral health across the region. Dental care in other former British territories, including Hong Kong and Singapore, is also superior to many other parts of Asia, she says. China is one country in need of better care: the latest survey found that 94 percent of the population suffers from some kind of dental problem, but there are only about 100 dentists for every million people, compared to 1,736 per million in Singapore.

Imperfect Coverage

While the mouth is not separate from the rest of the body, most insurance companies treat it that way, and both checkup and treatment costs can be prohibitive. The Affordable Care Act, which took effect in 2014, gave low-income children in the U.S. greater access to dental care through the Medicaid program. However, it didn’t bestow dental care on everyone. Medicaid is administered by individual states, and while most pay for emergency dental services for poor adults—such as dealing with a broken or abscessed tooth—fewer than half provide comprehensive or preventative care such as cleaning and scaling. Five states—California, Colorado, Illinois, South Carolina, and Washington—added dental coverage as part of the Affordable Care Act, but have struggled to pay for it.

It all comes down to money. State legislatures find it hard to come up with the tax dollars to pay for Medicaid dental coverage, Summerhays says, adding that many dentists are reluctant to see Medicaid patients because it places a financial strain on their practice. In California, reimbursement to dentists is just 30 cents on the dollar; in Illinois, it’s less than the cost of dental supplies. The “Santa Fe group,” a consortium of academics and business leaders, are lobbying to expand Medicaid coverage, arguing that it will improve overall health—and more than pay for itself.

Although it’s not enough to address the scope of the problem, the Health Resources and Services Administration announced in June 2016 that clinics in 47 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico will receive an extra $156 million in oral health funding, allowing them to hire about 1,600 new dental professionals to treat 785,000 new patients.

Countries with government-sponsored health coverage don’t always fare better. Coverage in Canada, for instance, is very similar to the U.S., Vujicic says, and perhaps not as wide, since there is no equivalent for care to low-income children. The publicly-financed system covers only a specific subset of dental surgeries performed in hospitals, and provides limited benefits for seniors and First Nations people. For the most part, oral care is excluded, and about two-thirds of Canadians pay for private dental insurance. Across the Atlantic, the U.K.’s National Health Service includes most types of dental care, but patients pay half. In fact, dental care is financed through out-of-pocket spending and private insurance in almost all of the world’s 35 member countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Only two members, Japan and the Slovak Republic, offer wide, state-funded coverage.

Despite the challenges, dental care is likely to evolve rapidly, the experts say. Some of that progress will come through new technologies, such as breath analyzers that can detect periodontal disease and saliva tests that identify oral infections. Greater understanding of the biology of oral and other diseases—in combination with public education that teaches dental hygiene—will help to diminish rates of dental disease. And some insurance companies are beginning to consider the notion that paying for dentistry may lower medical costs overall by preventing serious, costly conditions. “Things are going to change very rapidly in the next 10, 20 years,” predicts the ADA’s Summerhays.

Meanwhile, Kadir is collaborating with international organizations from her home base in Malaysia. Her hope: in a decade, most of the world will have the same access to quality dental care that’s available to citizens in her own country.

Credits: Michael Glenwood Gibbs, George Retseck